Interview with Tod Machover

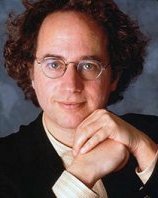

Interview with Tod MachoverBy Peter Stenshoel

Transcribed by Frank C. Bertrand

This is Peter Stenshoel. Philip K. Dick's work has been made into movies, plays and radio plays. But perhaps one of the more astonishing Dick mutations is the opera Valis composed by Tod Machover. It received its premier in France at the Pompidou Center the first week of December 1987.

TM: I'm not a big science fiction reader but when I was a kid the one science fiction writer I did read a certain amount of was Philip K. Dick. And when I was a teenager the book that had impressed me the most was Man in the High Castle; that really stuck with me. So pretty early on in the project I decided to go to an English bookstore in Paris and look through the Philip K. Dick section just because I had always admired his stuff. I hadn't read any in a long time. And it was totally by accident – I'd never heard of Valis – they happened to have a paperback copy of the first edition. Again, this was probably '83. And it was one of those things, I picked it up and I saw Philip K. Dick and it was this kind of a tacky cover but it was interesting because it was a cover with I think the original one had Christ on the cross built into a rocket or something like that...

TM: I just opened it up and started reading the beginning and after about – it's one of those funny things that happens – after about two or three pages, the combination of what it was about, the mixture of humor and real depth and pain, the fact that it was realistic but also about some very complex things, all of that together I said certainly I have to read the whole book but I knew almost immediately that it was what I wanted to work on. So that's exactly what happened.

PS: In the whole process of right from the beginning and through the staging of did you notice any synchronistic occurrences happening at all in regard to this?

TM: Well, let's see, there were a lot of actually kind of interesting things. And I won't say why or what. In fact I'm not even sure I can remember all of them right now. But the one I remember the strongest was actually pretty funny which was Catherine Ikam and I had been talking about the project. I had already decided on Valis and we're starting work on it, and I was still living in Paris. Bill Raymond came to Paris. There's a place in Paris called The American Center which is a sort of performance center. And Bill Raymond came to do a theater piece. It was actually a theater piece where he plays Ulysses S. Grant; it's a kind of monologue. I'm not a big theater fan myself but I went to this and was absolutely, I thought it was just great. So it impressed me a great deal. And I had no idea who he was, never had met him before. About a couple of weeks after that it all of a sudden occurred to me, you know, my god this guy would be fantastic to work on this project because there was something about his presence on stage that reminded me a little bit of the Philip K. Dick Horselover Fat character - just something about it resonated. And I said, look he lived in New York and I decided to call him up. So I just called him out of the blue, he didn't know who I was at all. And I said I was going to be in New York, could we sit down and talk. I was working on a kind of nutty project and wanted to tell him about it. So we met pretty soon after that in New York and it was one of these really weird things when I said, you know this is a kind of strange project. I'm working on this thing, you probably don't know Philip K. Dick, or have you heard of him? And he said, Philip K. Dick, my god, not only have I heard of him but I'm working on a Philip K. Dick project right now. In fact he was working on an adaptation of Flow My Tears for theater right at that time. And he said, not only that my wife was one of Philip K. Dick's best friends and I knew Philip K. Dick. And this whole thing unraveled where he was even more involved in Philip K. Dick at that point than I was and knew all about it and was involved in a theater project. And that was really odd because it was totally out of the blue that I'd picked him. Actually another thing that struck me was when I went to try to find out how to get the rights to base an opera on Valis. And it took me a while, but I finally got to Russell Galen who, as you probably know, is Philip K. Dick's, was his agent and is now in charge of the literary estate. It was really hard to get an appointment and again they usually handle movie rights. I was sort of expecting him to say well, you know, for an opera I don't know. Anyway, I went in and just said to him I think this is a fantastic book and I'm interested in writing an opera on Valis and it's going to sort of take this form, blah, blah, blah. And I totally expected him to say, well, it's a nice idea but we're not really interested. Instead he said well, you know you probably don't know this but I wasn't only Philip K. Dick's executor and his agent but we were really close friends. And not only that when he was writing Valis he was quite depressed a lot of the time and he use to call me about twice a day for a year and a half when he was working on it. And well I had to keep stopping working and I sort of talked to him every day while he was working on that book. Not only that Valis at that point in '82, '83 wasn't really all that popular, certainly not outside of fairly small Philip K. Dick circles. And he said you know a lot of people have mixed feelings about Valis. But you know I agree with you, I think it's his masterpiece and I'd love to see a treatment of it. And you probably don't realize this, or you didn't notice, but Valis was dedicated to me. Then all of a sudden I made the connections between who this guy was. There were a lot of things like that, a lot of people especially, who I kind of got in touch with without having any idea who they were, who had somehow been touched by this particular book and the whole project meant something to them. So I could go on and on but there were actually a lot of things, more than any project I've ever worked on.

PS: Is there a reason why maybe we might want to start paying more attention to Dick in your opinion?

I think that Dick had the courage and either the real seriousness of purpose and also the sense of humor - that's what I love so much about his work - to say that even though it seems like a hopeless situation to figure out - to say that there is in fact some deep spiritual or human reason to try to find what makes human experience more similar than dissimilar, both in different historical periods but between different kinds of people. You know this idea that what you see on the surface, which is basically the difference, is not the greatest truth. I think that's actually not a very fashionable idea right now and I think that ever more than ten years ago - I think there's a period in the 80s where it sort of seemed like through our media and communications there'd be a kind of facile way of connecting people, a sort of passivity and turning on your cable TV and seeing what's going on today in Tokyo or in Europe and you sort of feel like you can take all this stuff in. But in fact I think what we're seeing now is exactly what Dick predicted, which is that it ain't that easy, that if you look below the surface there's this incredible sense of horror and pain and panic that you sense when you get hit with this pink light. And I think the pink light is realizing how deep the fragmentation is. I think that what Dick's whole life work represents is the courage to keep looking for how things stick together. And I do believe that that is the task of our times and will be for the future, to not give up that search. I think that is his late books what he expressed so beautifully was the little glimpses of what makes it worth keeping looking and the courage to keep looking even when, kind of the way Horselover Fat ends up at the end of Valis, his whole, he had enough of a glimpse of Sophia and some kind of truth that he doesn't give up. On the other hand he hasn't found a way to sustain that level of realization. To me I don't think anybody's expressed it better.

PS: Very good. Thank you so much.

TM: Good to talk with you.

PS: Yes, good to talk to you too.

TM: Bye, bye.

PS: You just heard Tod Machover speaking of his opera Valis based on Philip K. Dick's stunning work Valis. I'm Peter Stenshoel and my thanks to Mr. Machover for taking some time during his busy schedule to speak about these things.

Tod Machover is the Director of Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Media Lab and he's also an Associate Professor of Music and Media at that institution. Dick's fascination with the human potential of robotics and vice versa are echoed in Machover's invention known as the "Conductor's Glove" or "dexterous hand mastered" which, fitted onto one's hand, allows one to assume control of an entire music studio. I spoke recently with Machover about his opera Valis and about Philip K. Dick. Persons mentioned in this interview include Catherine Ikam, the French installation artist, and Mabou Mines and ZBS actor and producer, Bill Raymond. Both of these individuals were involved in the original production. Here then is Tod Machover.

PS:...Big gantry.

PS:...Big gantry.

TM: I think one of the interesting things about Dick is that actually there are so many things that he felt and expressed in his books that are not so much messages as really clear pictures of where the world is going, often frighteningly so. I think he is probably one of the most visionary authors that's been around in the last fifty years or so. The part of his message I think that resonated most with me, and I think is very important, is one I think he struggles with in Valis and all those books at the end of his life, is how is it possible to keep some sense of hope when the world and most of our personal situations are in such an extreme state of pain. And the particular situation that I think he describes in Valis, I mean to me it's what the whole pink light experience and his reaction to it means, is we live in a world that is becoming in fact more and more fragmented, more and more complex. I mean you don't have to have a pink light experience to realize that there is too much information to not only be aware of but to make any kind of sense out of. What we've seen nobody really would have expected like three or four years ago - that the kinds of thing we're seeing in eastern Europe now - the world, instead of moving towards some kind of greater communication actually, is again breaking up into little pieces where nobody seems to understand each other. There's an incredible amount of hatred and really bad feeling is surfacing. There's this incredible feeling of the world being not only too complex for any one person to make sense out of but also dangerously complex, to the point where people will not only not understand each other but end up hating each other and being absolutely crushed under the burden of just trying to make sense with how much there is to know. And to me that's kind of what being bombarded with this pink light and too much information means.

TM: I think one of the interesting things about Dick is that actually there are so many things that he felt and expressed in his books that are not so much messages as really clear pictures of where the world is going, often frighteningly so. I think he is probably one of the most visionary authors that's been around in the last fifty years or so. The part of his message I think that resonated most with me, and I think is very important, is one I think he struggles with in Valis and all those books at the end of his life, is how is it possible to keep some sense of hope when the world and most of our personal situations are in such an extreme state of pain. And the particular situation that I think he describes in Valis, I mean to me it's what the whole pink light experience and his reaction to it means, is we live in a world that is becoming in fact more and more fragmented, more and more complex. I mean you don't have to have a pink light experience to realize that there is too much information to not only be aware of but to make any kind of sense out of. What we've seen nobody really would have expected like three or four years ago - that the kinds of thing we're seeing in eastern Europe now - the world, instead of moving towards some kind of greater communication actually, is again breaking up into little pieces where nobody seems to understand each other. There's an incredible amount of hatred and really bad feeling is surfacing. There's this incredible feeling of the world being not only too complex for any one person to make sense out of but also dangerously complex, to the point where people will not only not understand each other but end up hating each other and being absolutely crushed under the burden of just trying to make sense with how much there is to know. And to me that's kind of what being bombarded with this pink light and too much information means.

Additional Resources:

MIT Media Lab Tod Machover page with 14 links to other info

Valis Opera page with Quicktime video

Valis opera CD, at Bridge Records, with MP3 audio sample

Review of VALIS, by James Schellenberg

Valis points to exciting possibilities for growth of opera, by Jonathan Richmond